Author’s Note to the Reader ......................................................7

Preface .....................................................................................9

Foreward .................................................................................11

Chapter One My Krakow ..........................................................15

Chapter Two The Fuss Family ...................................................23

Chapter Three War Comes to Us................................................29

Chapter Four Bronowice ...........................................................45

Chapter Five The Ghetto in Krakow ...........................................51

Chapter Six Plaszow...................................................................67

Chapter Seven High Holidays in Plaszow .....................................79

Chapter Eight Skarzysko.............................................................83

Chapter Nine Leipzig ................................................................103

Chapter Ten Death March ........................................................113

Chapter Eleven Liberation ........................................................119

Chapter Twelve Returning to Poland .........................................127

Chapter Thirteen Israel ............................................................147

Chapter Fourteen Emigration ...................................................165

Chapter Fifteen New York..........................................................173

Chapter Sixteen West New York ................................................179

Chapter Seventeen Franklin Township .......................................187

Chapter Eighteen Watchung ......................................................193

Chapter Nineteen New Life ........................................................197

Chapter Twenty EAR ..................................................................211

Chapter Twenty-One Mother ......................................................215

Chapter Twenty-Two Poland Revisited..........................................225

Chapter Twenty-Three Olympics .................................................235

Chapter Twenty-Four Temple Sholom: Construction.....................241

Chapter Twenty-Five Temple Sholom: Presidency ........................247

Chapter Twenty-Six Liberation Monument ...................................253

Chapter Twenty-Seven After the Liberation Monument ................259

Chapter Twenty-Eight Opera........................................................265

Chapter Twenty-Nine Around the World .......................................271

Chapter Thirty Holocaust Education .............................................279

Chapter Thirty-One The Vatican ...................................................287

Chapter Thirty-Two Yad Vashem...................................................295

Chapter Thirty-Three Final Reflections ..........................................305

Family Album ..............................................................................311

Acknowledgments........................................................................326

Chapter Six -- Plaszow

There was an alternative to Plaszow: instant death. Outside the gates of the labor-concentration camp, the Nazis methodically selected those among us—only 8,000 made the grade—who appeared able to work. The “unprivileged” were marched up to a hill inside the confines of Plaszow. They were ordered to dig long ditches, and then undress completely, since the Germans did not want to waste clothes on dead bodies. Humiliated and afraid, the victims were commanded to line up on the edge of the ditch, where machine gun shots—one per person—methodically toppled them, dead or alive, into their final resting places. The blast of bullets signaled their demise.

Those of us who remained were taken on a three-mile march that lasted a seeming eternity, finally entering the gates of hell: Plaszow. Barracks the length of long barns—our sleeping quarters—were grim and crowded. Now we were to share a space not with nine people, but a few hundred women. Narrow bunk beds, the width of army cots, lined the wooden walls three layers high, each one accommodating two women. SS guards in tailored uniforms and shiny boots swarmed around the camp, guns hanging over their shoulders as a warning against any act of disobedience. There could be no hesitation in carrying out any order they might shout. The speed with which their fingers could find the trigger could outrace a bolt of lightning.

Awaiting the construction of our workplaces, where we would advance the German war effort, our captors invented a slew of meaningless and exhausting jobs in our initial days in Plaszow. At first we were assigned to carry boulders from one side of the road to the other. When we finished, we were commanded to carry them back to the original side. We were never permitted to be idle except when we slept at night.

My life-saving defense mechanism was an ingrained, unyielding attitude to make the best of any situation. While the physical labor broke the backs and spirits of many of those I worked with, I viewed it as an opportunity to be outside in the fresh air as opposed to the dingy, stuffy brush factory where I had worked in the ghetto. The weather was beautiful, and the warm sun felt good on my back.

Within a few weeks the useless tasks yielded to work aimed at bolstering the German military. Work barracks were erected, and mother and I resumed our jobs making brushes at a Plaszow work barracks. Others were assigned to a garment-factory barracks making military uniforms or to mechanical workshops.

The barracks were built with large windows, which allowed the guards to exercise control over us from the outside. The windows faced a road that led to the hill where the mass graves were dug. The liquidation of the ghetto, with its thousands of inhabitants, took weeks, and from the windows of our work barracks we witnessed long lines of people streaming up the hill from where we could hear the gunshots. We always knew when the ditches were too full because the gunfire would be delayed—until new graves were dug.

Recognizing faces in the parade of people marching to their tormented deaths was the most insufferable part of this terrible event. One day I saw the twin brother of Uncle Julek Hilfstein among the victims. I could hardly contain the blood racing through my veins. I felt helpless watching him marching so downtrodden. He must have sensed the pointlessness of protesting, which would have brought severe beatings before his death sentence, and he walked with resignation to his violent end.

Knowing the fate suffered by many of our family members, friends, and neighbors, we considered nothing more important than staying alive in the moment. Delaying death became our main goal.

To my eyes the guards appeared enormous. Most striking and frightening was the commandant, a man named Amon Ghett, who carried a big whip he was always ready to use. Ghett marched with a harlequin Great Dane and a menacing entourage whose loud laughter sent shivers down our spines. The sadistic satisfaction they derived from haphazard, spontaneous beatings or shootings of inmates was intended to strip us of any semblance of humanity.

In Plaszow, the reality of this war, of this Holocaust, finally hit us. We were captives of monsters.

One sunny morning we received a surprise order: to clean and whitewash the exterior of our barracks, buildings about which our captors had never cared. We were even ordered to dress neatly and comb our hair carefully. The commands puzzled us: amid such horror, why should attention be paid to appearances?

The mystery was soon solved. A large delegation of the Red Cross International had arrived to inspect the conditions of the facility. The observers saw what they perceived as a healthy, vigorous workforce carrying stones. Despite viewing young girls and other frail people bending under the weight of carts loaded with heavy stones, they somehow concluded we were being treated decently. They did not even criticize the three tiers of bunk beds made of hard board without bedding, each the size of an army cot and accommodating two people.

The Red Cross officials did not go to the kitchen to see the gray slop with mysterious floating objects that was called “soup,” nor did they taste the gooey brick which was our bread. And they did not walk up the hill to see the ditches full of freshly killed corpses, some of them still barely alive.

Before that day we had worshipped the Red Cross as a protector of human rights, but after their inspection, we lost hope. We realized that not even the Red Cross considered us human, and that there was no one left to speak on our behalf. We felt totally abandoned.

News of Niusia and father sifted to us from people who came to Plaszow from Emalia, the factory connected with the Barakenbau lumber yard, where they had been assigned. Emalia was not far from the ghetto, yet the distance was impenetrable for us. We knew they were alive. Despite the irrationality of our dreams, every day we hoped to see them.

Several weeks after arriving at Plaszow, on our day off, what felt like a miracle happened: Father appeared at Plaszow together with a group of laborers from Emalia. They had been given permission to pay us a visit.

I was simultaneously overjoyed and heartbroken by father’s appearance. He was obviously exhausted from hard labor. His clothes hung on his emaciated body, and his eyes had lost the spark I had loved so much. He attempted to smile, but despair filled the lines in his face. He wore a knapsack in which he brought a pot of milk soup with dumplings; he had wrapped the pot beneath his clothes to keep its contents warm. Access to a stove had not been denied him, though I could hardly imagine how he had been able to gather the ingredients, cook a soup, and risk the danger of sneaking it to us.

Mother, father, and I sat in virtual silence, relishing the moment even more than the delicious soup. Throughout my life, father’s love had sustained me morally and emotionally in the worst circumstances. I had always envisioned him as a cuddly, loving man with a great sense of humor. But on that day in Plaszow father was not laughing.

Father filled in the blanks of our curiosity about him and Niusia. He explained they had been assigned to work at Emalia with Christians imprisoned by the Nazis. Mrs. Podworska still managed to smuggle some money to them, and that was how they were able to purchase a limited amount of food on the black market.

At the end of the day mother and I felt justified in the dreams we had nurtured, of setting eyes once again on father and Niusia. We looked forward to a visit from Niusia in the same way father had come to Plaszow, and we eagerly awaited father’s return. But there was no next visit. Nor was there ever a visit to Plaszow from Niusia.

Father, however, had received a personal reward that day in Plaszow. He had watched mother and me imbibe with relish the soup he would provide for us, for the last time. This milk-dumpling soup was the most delicious treat I ever ate. So much love had been poured into it.

The Germans kept meticulous count of the people living in the barracks. Each morning we were all required to stand in formation in front of our barracks until every person was accounted for. Sometimes the numbers did not check exactly, and the count took many hours. Every night someone was required to be on duty, prepared to give a count of all the inmates in the barracks. The report had to be recited in German, using precise wording and rhythm.

Once, when it was my turn on duty from 3 to 5 a.m., the welcome nighttime quiet suddenly yielded to the loud, acrimonious sounds of shooting and the heavy footsteps of soldiers’ boots. The doors of our barracks were thrown open, and Commandant Amon Ghett and his entourage stormed into the room. I don’t know how tall he was, but in that moment he appeared to be more than 10 feet tall, hovering over me with his black-and-white harlequin Great Dane at his side.

Enveloped in fear and panic, with my memory momentarily frozen, I realized my life depended upon a correct report, which consisted of a specific greeting and a count of women in the barrack that night. I jumped to my feet, stood at attention, and blurted my report in German― in a daze. I felt as if an unknown voice was speaking for me.

Ghett and company left as they had come, without uttering a word. Once again the sound of a few hundred women sleeping peacefully, unaware of the drama that had just unfolded, filled the barracks. It was springtime. A hint of the dawn’s pink sunrise streamed through the window, the smell of early morning dew seeped through the cracks in the walls, and a bird sang its high-pitched song. The season’s promises of renewal flourished on the other side of the barbed wires, cut off from the climate that relentlessly persisted on this side.

How I envied the birds their freedom! A month after my liberation in 1945 I took an American reporter on a tour of the Auschwitz death camp. In the museum the Poles had erected on the site, I saw a painting depicting a silhouette of a man resting his tired body on a shovel in front of barbed-wire fences, longingly looking at a single bird on a tree outside the fence. How well I understood the scene. It could have been me the night of Ghett’s visit to the barracks. . .

Despite living in constant fear I could not keep myself from small acts of rebellion. Perhaps it came with the nature of my age, or maybe it was my way of proving that I still had some control. One day we were ordered to turn in all the jewelry still left in our possession. The one thing I refused to part with was a beautiful sterling silver dachshund on a chain, a prized gift from my beloved cousin, Salek.

Of all my cousins, I adored Salek the most. Only six years older than me, my six-foot-tall, blue-eyed, blond cousin with the physique of Hollywood actor Victor Mature, was the heartthrob of all my girlfriends. Despite our age difference he often included me in his outings. Salek was a member of Maccabi, a Jewish sports club. With him, at the age of nine, I went skiing for the first time. We embarked on the adventure early in the morning, going to the little Krakow hills of Podgorze, where later the ghetto was built. Salek broke his ski at the beginning of the day, but not willing to give up, we went to his workshop where he spent the whole day repairing it. We were oblivious to time and did not return home until 10 p.m., much to the worry of my panic-stricken parents and relatives.

Though Salek was admittedly not the most reliable escort, the rebuke we received left me brokenhearted. I especially admired Salek’s courage. Just before the war broke out, groups of Polish students roamed Krakow’s streets, beating Jews. One day when Salek returned home he greeted my father with his lips tightly closed. It did not take long for my father to make a funny comment and Salek’s broad smile revealed two missing front teeth. My shocked father asked what had happened, and Salek replied: “Uncle, you should have seen my opponent!” We later learned that the Maccabi club had organized a bunch of strong young men, including Salek, to confront the attacking students. Jews were generally not inclined toward physical retaliation, and only a few participated. Salek’s chivalry sealed my perception of him as my greatest hero.

For my ninth birthday Salek presented me with one of my most cherished possessions. While it was not customary for children to have much jewelry, my cousin gave me a beautiful sterling silver dachshund on a chain. Until I was forced at the age of 14 in the Plaszow concentration camp to remove all my jewelry, the necklace never left my neck.

Declining to leave my treasure in the hands of the Nazis, I buried it next to my barracks and never saw it again. On my 65th birthday, my daughter Irene had a jeweler replicate the dachshund with great precision. I must have described it in vivid detail.

While this may seem an insignificant incident in the face of being constantly exposed to the sound of gunfire and the sight of people being tortured or killed, it gave me a feeling of satisfaction. Anyone in uniform was an adversary, even a Jew assigned to some kind of policing post. Initially some Jews had volunteered for this service as a way of protecting their families. While some of them maintained their humanity, others became as brutal as their German captors.

Our ranks were steadily decimated with ever-changing categories of people being marched to the hill. One day our captors took inmates they considered too young; the next day’s victims were those they decided were too old. It was impossible to determine which criterion they would employ each day. We focused on outguessing them, speculating on what to do to our appearances to fit the image we could only hope they would not want to destroy.

Since I was more assertive than mother I assumed control of family decisions. Mother was a strong woman, but her gentle disposition led her to avoid controversy. She had great confidence in me, which enhanced my own self-esteem even in those circumstances.

One day, seemingly out of the blue, I insisted that it would be safer for mother to conceal her white-gray hair. Always meticulously swept back, her hair had been that color throughout my life. Mother was elegant but modest, never using cosmetics, and she was repulsed by the thought of dyeing her hair. Moreover, the payment for such a service was our meager day’s bread ration. Nonetheless, I insisted. She submitted to the process, which was performed by another inmate.

Several days later gray-haired people were marched to the death-hill, considered by the Germans to be too old to work. Once again, mother was granted an extension of life.

Few inmates attempted to escape Plaszow. The biggest impediment to escape was the camp’s location in open fields, surrounded by two rows of electric barbed wires, with watchtowers equipped with searchlights situated every few hundred feet of the camp’s perimeter. The entire surrounding area was brightly lit and guarded by vicious, roaming dogs. The camp was also located a long distance from any area where one could seek shelter. People living outside the camp were afraid to hide us. The Germans had imposed the death penalty for them and their families in retribution for any such act. Moreover, some people who lived in the areas outside the camp were ready to report runaways in exchange for the reward of five pounds of sugar, or perhaps just the satisfaction of turning in a Jew.

The greatest deterrent to escape, however, was the collective punishments the Germans would inflict on all the camp inmates. Cognizant of the sense of community among Jews, the Nazis held everyone collectively accountable for any infractions of the rules. Each escape cost the lives of many people who knew nothing about it. Daily head counts in the mornings and evenings revealed missing inmates within hours.

I knew very little about the underground or its activities, other than that it existed. Few people wanted to confide such dangerous information in me, a 14-year-old. And I preferred not to be privy to secrets that could put anybody in jeopardy.

One beautiful, sunny day, three young men who, we believed, were connected to the underground, escaped. It took only hours for the Germans to capture them. Ghett decided to make an example of the consequences of their behavior. We were required to gather in front of three gallows atop tall platforms, surrounded by so many uniformed, gun-toting soldiers, it appeared as if the entire German army were present.

A public hanging was announced. Just before joining the ranks of Jews ordered to witness it, I convinced mother to hide on a top bunk bed. She assumed I would join her, but I was too scared to hide. Being in the open and seeing what was happening gave me a false sense of security. In the last minute I slipped out. There was no time to argue, and we could not bring attention to our plot. Despite the realities surrounding me I believed myself to be as invincible as most teenagers. I experienced a sense of great responsibility for my mother, whom I saw as being more vulnerable than me, and my somewhat spontaneous actions were too unpredictable for her to control. Trusting my instincts was my modus operandi, which proved to be as effective as any other.

Jewish policeman Iciu Salz, the youngest son of the brush factory Hasidic bosses, was selected to do the hanging. Though in the factory he was known for his brutality toward the Jews, this job exceeded any behavior to which he might have acquiesced. Yet he had no choice. We stood for what seemed like hours around the gallows, required to witness the procedure.

One of the boys emerged on the tall platform with his head held high proudly reciting the Sh’ma, a sacred Jewish prayer declaring unity with God. The other was hung instantly but his noose broke on the first attempt. Despite the international convention requiring a hanging victim to be released in this circumstance, the boy was brought to the noose a second time. All the while he never stopped reciting the Sh’ma. I admired the dignity with which he died this most awful death.

The torture did not end with the deaths of the three who had unsuccessfully attempted to escape. After the hangings we were required to march single-file in front of the gallows, our heads turned toward the bodies. As we passed by, each tenth person was pulled from our ranks and laid on a table to receive a lashing of horse-leather whips against their bare buttocks, tearing their skin mercilessly. My cousin, Esther Wolf, Joel’s mother, was among those beaten that day.

It took weeks for the whipped bodies to heal, and infections exacerbated by malnutrition set in. Yet no one was permitted to stop working for a day. The punishment served to ingrain the lesson of the futility of rebellion or escape.

This experience hastened my maturity. I resolved not to develop relationships with boys or to form any attachments that could expose me to additional losses or hurt. Having to worry about the loss of my immediate family was more than I could handle. I started to build a wall around myself, a self-created cocoon.

The work in the brush factory was consuming, and I responded by setting personal goals of bettering my skills. This focus, together with preserving my only dress—a black cotton dirndl with white polka dots, red piping, a fitted bodice, and a gathered skirt—enabled me to maintain a sense of self-worth.

My brush-making abilities became known to my bosses, and when an order came from Ghett to produce brushes for grooming his horse, I was selected to make them. I felt proud of the quality of my work, caring little about the destination of the product. I did not realize, however, that with the assignment came an order to deliver the brushes in person to Ghett’s house. This was a frightening prospect.

The commandant’s imposing white house stood down the hill, isolated from the camp. It was known for famous parties where factory owner Oskar Shindler was entertained along with notable Nazi henchmen. In the midst of the slaughterhouse where we were imprisoned was this oasis, equipped with a sophisticated library and record collection. Apparently Ghett and his cohorts were unfazed by the contradiction between their island culture amid a sea of atrocities.

Not given a choice, I frightfully embarked on the walk to Ghett’s forbidden world. I held my breath until I reached the spectacular, large kitchen where I was told to deliver the brushes. The employees in white jackets hovered over steaming pots of fragrant food, which at that moment was not at all tempting. I wanted only to get out alive. One never knew when an officer would get an urge to use me as target practice for entertainment.

Fortunately I did not encounter any officers. I promptly handed over the brushes and started on my return trek. The starving diet of the inmates was no secret to the cooks, however, and one gave me a package of ground meat, wrapped in paper. How exciting was the prospect of bringing real food to mother, even if we had to eat it raw. I flattened the package and slipped it securely under the bodice of my dress, on my stomach. I feared that if it fell out or was detected, penalties would be suffered not only by me, but by the well-intentioned cook as well.

I felt almost giddy. Suddenly as I exited the kitchen, Ghett’s Great Dane, the black and white giant, appeared, heading straight for me. For a second I believed that my fantasies of feasting on the raw meat would give way to the dog feasting on me. He approached me slowly, smelling around my body, but miraculously he went on his way, leaving me to go back to the barracks with my treasure. Mother and I shared the meat, relishing every morsel. This was the greatest culinary treat we enjoyed at Plaszow.

After the first few months at Plaszow, the initial frenzy of activities subsided and we settled into daily routines. Amid the constant shooting and hunger to which we almost became adjusted, we worked 12-hour shifts, alternating days and nights. Summer was quickly coming to an end, and the prospect of winter was intimidating. Light shone through cracks in the wallboards where we knew the cold of winter would settle. Undoubtedly heating would be very sparse. Still, we believed that now the Germans would leave us alone. We feared any new move.

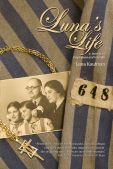

Author, speaker, Holocaust survivor and humanitarian Luna Kaufman was the 2009 recipient of Doctor of Humane Letters, honoris causa, from Seton Hall University in South Orange, NJ, in recognition for her outstanding work in developing Jewish-Christian relations. The degree coincided with release of her memoir, Luna's Life: A Journey of Forgiveness and Triumph, in which she shares her personal experiences from her childhood in Poland to her adulthood that led her across three continents.

As a survivor of four years in concentration camps, Luna was fortunate to emerge with her mother and return to her hometown of Krakow, Poland determined to resume her life. Calling upon a tenacity that has characterized her life, Luna set out to complete her education that was interrupted prior to WWII while in the sixth grade. She managed to graduated from high school, followed by attaining a degree in musicology from one of Europe’s oldest universities, Jagelonian University in Krakow, Poland.

As she wrote in her memoir, “Those who know freedom understand the responsibilities that accompany this great value.”

Her first hurdle toward fulfilling those responsibilities was to escape from the Communist regime in Poland. Eventually, accompanied by her mother, an inseparable life's partner, they embarked on a three-day journey across Western Europe to Venice as one of the first Jewish groups permitted to leave the Iron Curtain. The train was sealed and guarded to prevent any passenger from escaping. In Venice, they were herded aboard a ship taking them to Israel.

After spending two years in Israel, Luna immigrated to the United States. Upon her arrival Luna quickly adapted to this very different culture. Despite her limited English, she was hired by a New York bank. Since typing was a requirement of the job and with her indomitable spirit (“There are few obstacles I cannot imagine finding ways to conquer.), she taught herself over a weekend on a rented typewriter. From that point forward, Luna absorbed all the information about the American lifestyle that her co-workers offered.

Following her marriage and becoming a mother of three children, Luna moved her family to Watchung, NJ where, after five years of being separated from her mother, the two were finally reunited when her mother finaly received a visa to the States. In the 1960s, Luna launched a remarkable career of civic accomplishments, first as a board member of the League of Women Voters and as Girl Scout leader who began to introduce Jewish traditions to Christian children and Christian traditions to Jewish children. Luna soon began lecturing on the topic of the Holocaust, emphaszing “How we lived, not how we died,” and helped organize the first Holocaust seminar for New Jersey public school teachers.

Elected as the first woman president in the 80-year-history of Temple Sholom in Plainfield, NJ, she was instrumental in commissioning “Flame,” a Holocaust memorial sculpture by internationally renowned sculptor Natan Rapoport. At the sculpture’s installation, New Jersey Governor Thomas H. Kean announced the formation of the New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education and appointed Luna as a charter member. The sculpture now hangs in the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Battery Park, New York City.

Luna's work with Governor Kean led to her appointment as a co-chairman for the installation of “Liberation,” another Rapoport sculpture of an American soldier carrying a limp survivor as he liberated a concentration camp. The unvailing attracted thousands of participants including ambassadors of many nationsand, today, overlooks the Statue of Liberty at New Jersey’s Liberty State Park. “This tribute to American G.I.s, an expression of gratitude, was a concept very dear to me,” says Luna.

Luna’s dedicated accomplishments have touched many facets of American life. Culturally, she served as president of the New Jersey State Opera, producing “Frederic Douglas,” an opera by Ulysses Kay, and she has served on the Newark Mayor's Task Force for the development of the New Jersey Performing Arts Center. An avid skier, Luna was a volunteer housing coordinator for the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, NY.

Luna's commitment to freedom and human rights is manifested in her constant efforts to promote an understanding of both he horrors of the Holocaust and as well as the sacrifices of the righteous Christians. Commited to fostering interfaith and interracial respect and harmony, she has worked tirelessly with the late Sister Rose Thering, a former nun and professor at Seton Hall University and one of the world's most outspoken advocates of religious accord—having led 58 trips to Israel to acquaint Christian leaders with the country. Sister Rose was one of the principal catalysts in the 1963 repudiation of anti-Semitism by Pope John XXIII and the Second Vatican Council.

In 200X Seton Hall established the Sister Rose Thering Endowment for Jewish-Christian studies. Luna, who has said, “My greatest desire is to be a Jewish counterpart of Sister Rose,” is a past chair of the Endowment. Today, Luna continues to strive for that accomplishment with her message of Jewish-Christian understanding.